Thinking of Korea

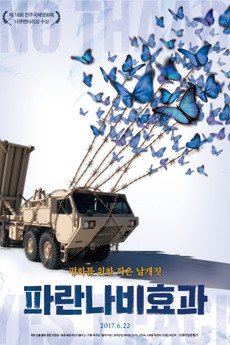

BY KIM TRAN[divide]On July 27th, 1953, the nation of Korea was divided into two separate entities along the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ). This division of governments and people ended a several year conflict that began during WWII. The Korean War (1950-1953) spurned the loss of over 1 million Chinese and Korean lives and a longstanding cold war between the United States and North Korea—with South Korea as a contested intermediary.Today, a part of the South Korean role in the cold war is housing the Terminal High Altitude Area Defense (THAAD) which detects and intercepts incoming ballistic missiles before they make contact. The US government installed THAAD in Soseongri, a small village, despite protests from children, elders and Won Buddhists who set up a shrine and vigil on the access road.Many have criticized THAAD because it even further militarizes South Korea and primarily seeks to protect American economic interests — as opposed to animals, people or land.During a Buddhist Peace Fellowship teach in called “Waging Peace in Korea,” Hella Organized Bay Area Koreans (HOBAK) highlighted that the THAAD installation site is sacred to Won Buddhists. Lifting up a symbol of the ongoing resistance against militarization in South Korea, BPF member and origami instructor Jun Hamamoto taught participants how to fold blue butterflies.This photo collage illustrates and represents the Block Build Be framework in anti-militarism efforts in Korea. Organizers and community members spanning the world are committed to blocking THAAD, building solidarity across borders & prison walls, and being devoted to creative art, sacred lands, and a dream of no more war.[divide style="2"]

BY KIM TRAN[divide]On July 27th, 1953, the nation of Korea was divided into two separate entities along the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ). This division of governments and people ended a several year conflict that began during WWII. The Korean War (1950-1953) spurned the loss of over 1 million Chinese and Korean lives and a longstanding cold war between the United States and North Korea—with South Korea as a contested intermediary.Today, a part of the South Korean role in the cold war is housing the Terminal High Altitude Area Defense (THAAD) which detects and intercepts incoming ballistic missiles before they make contact. The US government installed THAAD in Soseongri, a small village, despite protests from children, elders and Won Buddhists who set up a shrine and vigil on the access road.Many have criticized THAAD because it even further militarizes South Korea and primarily seeks to protect American economic interests — as opposed to animals, people or land.During a Buddhist Peace Fellowship teach in called “Waging Peace in Korea,” Hella Organized Bay Area Koreans (HOBAK) highlighted that the THAAD installation site is sacred to Won Buddhists. Lifting up a symbol of the ongoing resistance against militarization in South Korea, BPF member and origami instructor Jun Hamamoto taught participants how to fold blue butterflies.This photo collage illustrates and represents the Block Build Be framework in anti-militarism efforts in Korea. Organizers and community members spanning the world are committed to blocking THAAD, building solidarity across borders & prison walls, and being devoted to creative art, sacred lands, and a dream of no more war.[divide style="2"]

"We want to show that all these people are with you.

It's not a lost cause."

Michael Hong (pictured, left) is a member of HOBAK. In November, he and a delegation from HOBAK brought hundreds of these carefully folded origami gifts to Soseongri, where the US government began installing THAAD in the dead of night. Hong says:

Michael Hong (pictured, left) is a member of HOBAK. In November, he and a delegation from HOBAK brought hundreds of these carefully folded origami gifts to Soseongri, where the US government began installing THAAD in the dead of night. Hong says:

The blue butterflies were a symbol of this movement that arose in Korea as a result of the US forcing through this missile defense system that’s not meant to protect anyone in Korea — but US economic interests. The butterflies represent people from all different backgrounds coming together to support this small group of people fighting against the US military; which is an unbalanced fight.

Mike went to Korea twice last year in support of the community resisting THAAD. He describes the exchange of butterflies with the Korean activists as profound. "[HOBAK] brought all those butterflies and all these people just broke into tears.” Ultimately, Mike says the butterflies are a way of being in solidarity with Korea, the Korean people and all others facing the ongoing machine of imperialism. “We want to show that all these people are with you. It’s not a lost cause.”Despite waning media attention following the installation, the battle to stop THAAD persists amongst community members, elders, children, and religious leaders. Hong says that when he was in Korea, he saw “thousands of riot police fighting against these grandmas from a small farming town.” [divide style="2"]

[divide style="2"]

Blue Butterfly: a symbol of love,

peace, and resistance

In Korean culture, butterflies are traditionally a symbol of love, happiness and transformation. In the context of anti-imperialism in Korea, the blue butterfly expresses the historical and personal proximity of war; a longing for peace and community; and a visible way to raise awareness about the hard-fought resistance to THAAD.

In Korean culture, butterflies are traditionally a symbol of love, happiness and transformation. In the context of anti-imperialism in Korea, the blue butterfly expresses the historical and personal proximity of war; a longing for peace and community; and a visible way to raise awareness about the hard-fought resistance to THAAD. [divide style="2"]

[divide style="2"]

Folding with faith, sending solidarity

from behind bars

In contemporary politics, the butterfly has also come to mean transcendence of borders — whether state, national or carceral. Incarcerated men at San Quentin California State Prison, under the guidance of Jun Hamamoto (pictured, center), joined BPF's solidarity offering, folding over 200 of the butterflies sent with HOBAK to Korea. (Photo by Peter Merts Photography)[divide style="2"]

In contemporary politics, the butterfly has also come to mean transcendence of borders — whether state, national or carceral. Incarcerated men at San Quentin California State Prison, under the guidance of Jun Hamamoto (pictured, center), joined BPF's solidarity offering, folding over 200 of the butterflies sent with HOBAK to Korea. (Photo by Peter Merts Photography)[divide style="2"]

Thinking of families divided by wars, borders,

& imperialism

Samir Shrestha, another BPF member (pictured far left), made butterflies with his family while they were visiting from Nepal, with some help from his friend Jun Hamamoto. Shrestha took the opportunity to bring awareness about militarism in Korea to his younger sister. He cites the origami art as key for helping his sister engage with the conversation about international politics in a different way than usual.

Samir Shrestha, another BPF member (pictured far left), made butterflies with his family while they were visiting from Nepal, with some help from his friend Jun Hamamoto. Shrestha took the opportunity to bring awareness about militarism in Korea to his younger sister. He cites the origami art as key for helping his sister engage with the conversation about international politics in a different way than usual.

I'm thankful of this opportunity to be with family after so long, and thinking of so many people all over the world that don't get to see their families because of borders and the imperialist wars all over the world.