June Jordan's Love and Lifeforce: Dharma for my Iranian Homeland

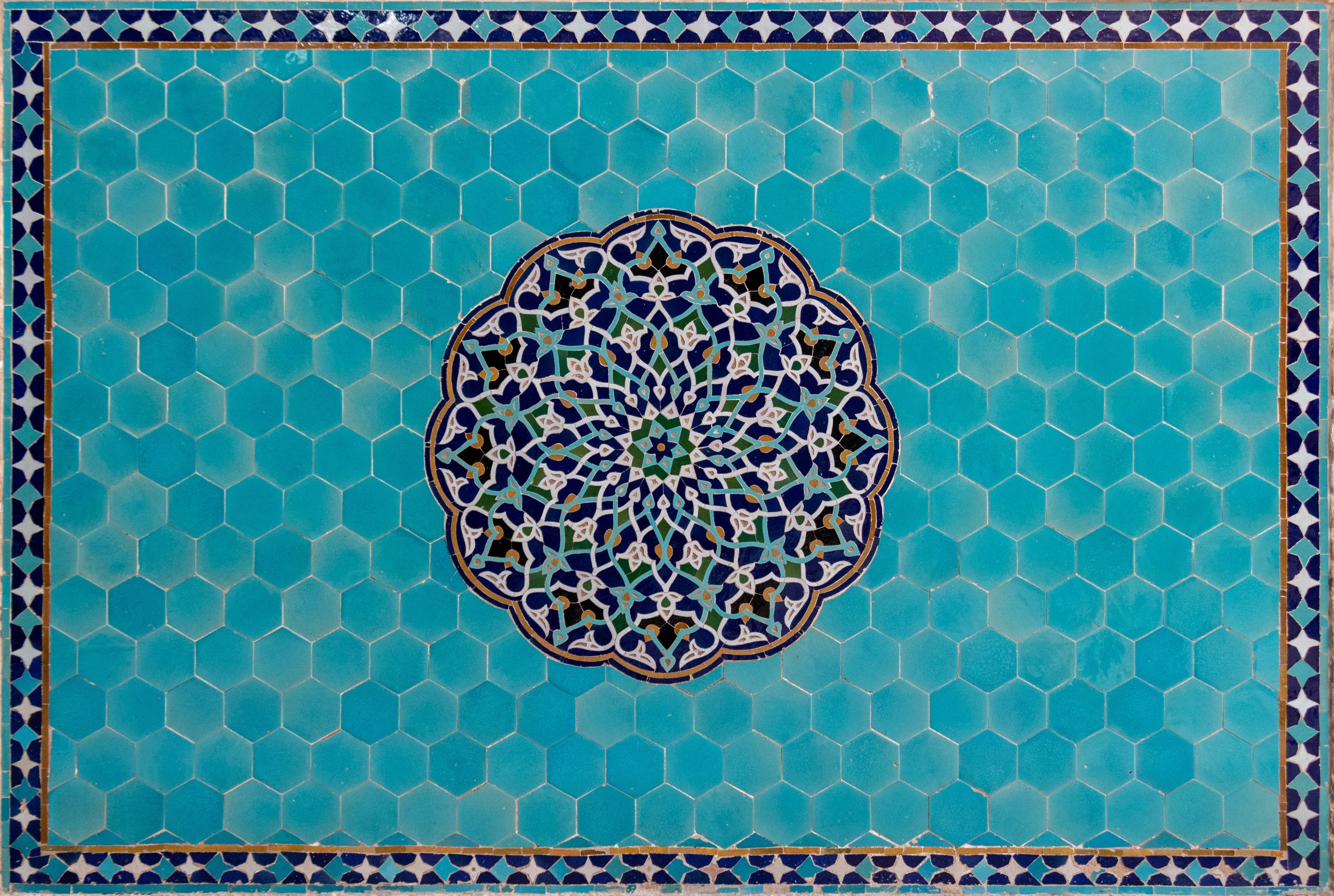

Photo by Mansour Kiaei, Unsplash.

Introduction

Last year, I participated in Buddhist Peace Fellowship's Build Block Be gathering (BBB) at the historic Highlander Center in New Market, TN. The gathering has had a lasting effect on my conceptualization of social transformation, as well as the relationship between personal and political change. I have continuously pondered the BBB framework — blocking harm, building alternatives, and being with spiritual wisdom and compassion — and found myself returning to it yet again in the wake of warmongering on Iran, my family’s homeland.

Photo by Ali Kokab, Unsplash.

I most identify as a builder. I am usually quick to imagine alternate possibilities, even if I don’t always have the capacity to act on them. But during the first few days of the Gregorian new year, while tensions between the U.S. and Iran mounted, I simply sank further and further into fear. I was also feeling the often-silenced pain of generations before me — for armed conflict has shaped my family in scarring ways. I wondered: How can such generational pain create conditions for a livable and sustainable future?

This question is precisely what led me to the Buddha's dharma around 2013. At Oakland’s East Bay Meditation Center and the people of color sangha (community) in particular, I learned practices for holding the dukkha (suffering) that I carry within myself, as well as the collective suffering of my contemporary moment.

As news of escalating threats to Iran and oppositional hashtags flooded the media, I tried to recall these practices, and turned to the dharma teaching that is June Jordan’s writings.

I re-read “Intifada Incantation: Poem 38 for b.b.L.” and thought about how poetry can build, block, and be. How it works language to transform what Jordan called, in a 1991 speech against the Gulf War, “the hellified lexicon of the killers ruling us.” I thought about how Jordan’s antiwar poem is also a love poem, spell, and chant. I thought about the incantatory potential of truth-telling and began to write the speech below.

Writing for a local protest didn’t take away my fear. However, the process did ground me in love as a “lifeforce”—to quote Jordan—that affirms the interconnectedness of all things. It also led to making more explicit interconnections, both at the protest and beyond. When I asked my dear friend Alexis Pauline Gumbs permission to use her chant of Jordan’s declaration, she organized an online writing workshop in which participants co-wrote a poem after “Intifada Incantation.”

Even as my fear remains, it is now accompanied by the tears, rage, and laughter of many.

Speech — January 5, 2020

My name is Tala Khanmalek, and I want to start by acknowledging that today we are gathered on the occupied territory of the Tongva people who have stewarded this land for generations. I am here as the descendent of Iranian immigrants, including refugees, and I believe that it is our responsibility to end the legacy of settler colonialism on this land and US state violence across the globe.

In my family, I have borne witness to the long-term effects of displacement. I have also borne witness to the long-term effects of war in my own lifetime, as have each of you. We already know that war leads to intergenerational trauma, to ecological destruction, to the conscription of mostly young people of color into the military, to increased sexual and gender-based violence, to the proliferation of the prison industrial complex and all other systems of oppression. We know this because the US has been at war since 2001, since 1492.

But just as I’m personally familiar with the consequences of imperialist violence, so too am I familiar with resilience, and the powers of survival, love, and mutual care. So today, even as we are here to protest and to speak out against warmongering—which relies on separating and dividing us—I ask everyone to also remember what we’re working to build instead.

What can we cultivate in our everyday lives as an antidote to war?

In the words of Black lesbian feminist poet June Jordan, “love is lifeforce.” Such love that June Jordan and other women of color feminists speak of, can and must be a daily practice.

And I say this, not naively but in all seriousness: because in these times, such radical love will motivate us to continue this fight; and can help us to sustain our interconnectedness and the interconnectedness of our struggles — the anti-war movement, the movement to protect Mauna Kea, the movement for Black lives and Palestinian self-determination…

When I think about our place within history, I know for certain that the love generated by those in the present and those who came before us will scaffold movements for change, justice, and peace.

Chant

by Alexis Pauline Gumbs, from June Jordan

When I say LOVE, You say LIFEFORCE!

LOVE!

LIFEFORCE!

LOVE!

LIFEFORCE!